China’s economic landscape is undergoing a profound transformation, marked by significant shifts in its growth engines. The evolving composition of China’s economic drivers is likely to have long-term implications for global economies and asset markets, necessitating a re-evaluation of which sectors and asset classes stand to gain or lose from these shifts.

The country’s aggregate growth beta – a measure of its economic sensitivity or correlation to global growth – is declining. This trend mirrors Japan’s experience in the 1990s and early 2000s, characterized by debt accumulation, ageing demographics, and a real estate bust (see Figure 1).

While we expect China’s growth beta to continue declining, similar to Japan’s trend in the 1990s, this does not diminish its importance in the global macroeconomic environment or financial markets. As the world’s second-largest economy, it retains dominant positions in global trade and commodity markets.

Figure 1: While China’s GDP growth beta decline echoes Japan’s experience in the 1990s, it retains the second-largest share of global GDP More Info

Source: Macrobond and PIMCO as of 15 August 2024. On the left-hand chart, the X-axis represents the number of quarters starting 1Q 1969 for Japan and 1Q 2000 for China.

Four key trends driving China’s growth over the secular horizon

We have identified four key trends that are set to drive China’s growth over the next three to five years:

- Credit growth reduction: The size and composition of China’s credit impulse (the change in new credit issued as a percentage of GDP) are changing. Historically, credit growth has been a major driver of China’s economic expansion, which has often been countercyclical and volatile. However, structural changes are expected to temper future credit growth. The central leadership, increasingly aware of the risks associated with high leverage, is curbing debt growth, particularly at the local government level. Additionally, declining profitability in the banking sector has reduced its capacity to support the same level of credit growth as in the past.

- Property sector contraction: Once a major engine of growth, the property sector is now a secular drag. We expect ageing demographics and significant overbuilt inventories to keep real estate investment and new starts weak. This decline in the property sector will have profound implications for both domestic and global markets, given that it has historically been a significant consumer of commodities, particularly iron ore, and a driver of economic activity.

- Increased manufacturing capacity: China is increasing its manufacturing capacity, shifting from a surplus in property construction to a surplus in manufacturing production. Unlike the property surplus, this new manufacturing surplus is being exported, making it a global challenge rather than just China’s. The government’s policy direction has been heavily focused on the supply side, with less emphasis on demand-side stimulus. This could lead to economic imbalances, with early signs of rapid capacity expansion in sectors such as electronic equipment and vehicle production aimed at gaining cost advantages. This shift is already intensifying competition with other advanced exporter countries for market share.

- Green energy investment: Investment in green energy is ramping up, signaling a shift towards sustainability and self-sufficiency. This trend will have varied implications for different sectors, particularly commodities. The rise in “green demand” for metals such as copper, aluminium, and nickel introduces a new dynamic, potentially offsetting the decline in traditional demand driven by the property sector’s slowdown.

China’s recent Third Plenum supports continuation of these trends

At its Third Plenum in July, a key meeting of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee, China’s leadership reaffirmed its long-term vision of pursuing reform and modernization.

Keyword analysis of the meeting’s communiqué shows a shift towards high-quality economic growth, particularly in advanced manufacturing and technological innovation. “Reform” remains the most common keyword, with “development” and “modernization” not far behind. There were limited additional easing measures outlined for the struggling property market. While there were more mentions about supporting domestic consumption, many of these measures are still supply-side led, such as providing greater variety and higher-quality services, rather than directly stimulating demand through fiscal transfers. We await further details on how these measures will be implemented. However, it was clear the government intends to boost the manufacturing sector and supply chains in more concrete ways, as well as technology sectors such as green energy, AI and biotech.

Given that the rhetoric largely represents a continuation of existing themes, we expect a continuation of the current trends driving China’s growth.

Implications for global markets

As China navigates the limits of debt-fueled growth and shifts towards new growth drivers, the effects of this transition will reverberate globally, affecting various sectors and countries over the secular horizon:

- Disinflationary impulse: China is likely to be an exporter of disinflation to the global economy over the secular horizon. This is due to the combination of slowing growth and increased manufacturing capacity. Persistent deflationary forces in China could translate into lower export prices, affecting global inflation trends. However, disinflationary forces are likely to affect emerging market (EM) countries more than developed economies. Imports from China represent a larger share of final consumption goods in EM, and core goods have a larger weight in the CPI basket in these countries than in developed economies.

- Commodity consumption: Despite the slowdown in growth, China’s consumption of key commodities is expected to increase, driven by investments in green energy. However, this increase will vary as the property sector continues to contract. For instance, while demand for iron ore may decline due to reduced steel production, demand for metals like copper and nickel could rise significantly due to their importance in green technologies.

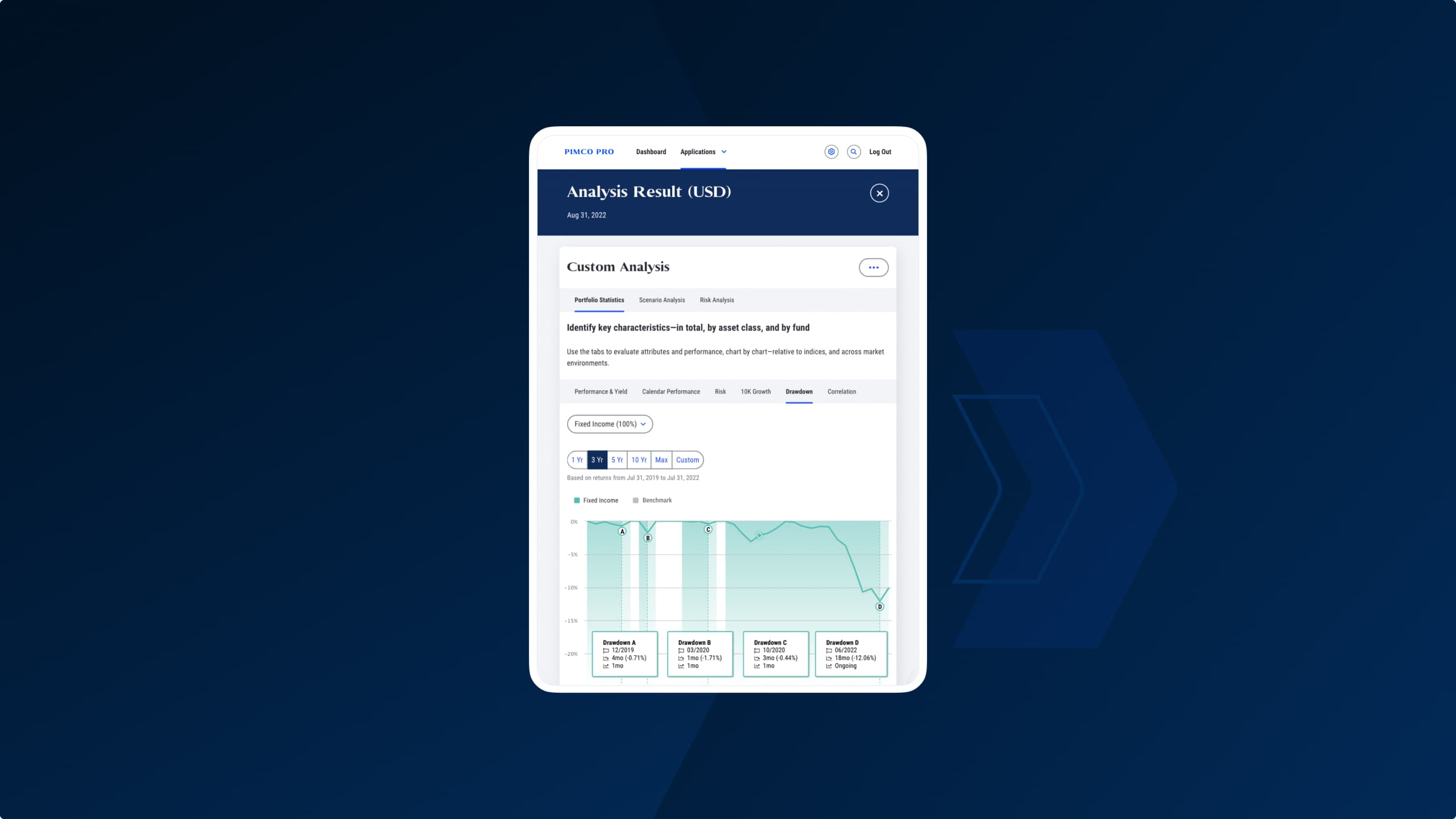

Australia will likely be among the most affected countries given that China is the largest buyer of its iron ore. The poor outlook for China’s property sector and the limitations on its ability to continue exporting excess manufactured steel could significantly impact iron ore demand, with potential knock-on effects on the Australian economy (see Figure 2). - Greater competition with other EM: China’s policy response to the property crisis, characterized by stimulating supply through export-led manufacturing growth more than boosting domestic demand, is leading to greater competition with other EM. By increasing manufacturing capacity and boosting exports, China is positioning itself to compete more aggressively in global markets. This strategy can lead to heightened competition for market share in various industries, particularly in manufacturing sectors where other EM also seek to expand exports. Consequently, this approach may intensify competitive pressures on these countries, potentially affecting their economic growth and market dynamics. One phenomenon we have already started to observe is that some emerging markets are exhibiting a reduced or even inverted beta to China’s growth. This contrasts with the positive correlation observed in the past couple of decades.

Figure 2: Declining iron ore prices put pressure on the Australian dollar More Info

Source: Bloomberg as of 15 August 2024

Structural changes will require investors to rethink their approach to China

In conclusion, China’s economic evolution will significantly affect global trade relations and the broader economy. As China shifts towards higher-quality growth, the composition of this growth will become more critical than the headline figures that investors have historically focused on. Investors must now evaluate which sectors stand to gain or lose from these economic changes by examining the long-term implications of the structural shifts driving China’s growth.